The internationally leading cardiovascular journal, the Journal of the American College of Cardiology (JACC, Impact Factor = 22.4), recently published a special issue on the Global Burden of Disease (GBD). The issue features a viewpoint article titled “Improving Global Cardiovascular Health by Integrating Primary and Community-Based Care”, led by Professor Lijing Yan from the Global Health Research Center at Duke Kunshan University.

The article was co-authored by a multidisciplinary team of experts, including Xingxing Chen, a jointly trained PhD student at Wuhan University and Duke Kunshan University; Gerald S. Bloomfield from Duke University; Tazeen H. Jafar from Duke–NUS Medical School; and Quang Ngoc Nguyen and Thanh Ho Kim from Hanoi Medical University in Vietnam. Together, the authors propose innovative solutions to address the global cardiovascular disease crisis.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) has become the leading cause of death and disability worldwide. In 2023 alone, CVD accounted for 438 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost globally. The burden is particularly severe in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where many nations are unlikely to achieve the Sustainable Development Goal of reducing premature CVD mortality by 30% by 2030.

At present, CVD management remains largely centered on cardiologist-led acute care. According to recent data, the global population of individuals living with CVD has reached 627 million, exacerbating the mismatch between the limited availability of specialist physicians and the growing patient population. Traditional healthcare models prioritize hospital-based treatment while neglecting lifelong prevention and management, as well as the social and cultural determinants of health—leaving them ill-equipped to respond to the globalized epidemic of cardiovascular disease.

The article argues that an integrated Primary and Community-based care (iPC) model may offer a new pathway for global cardiovascular health management.

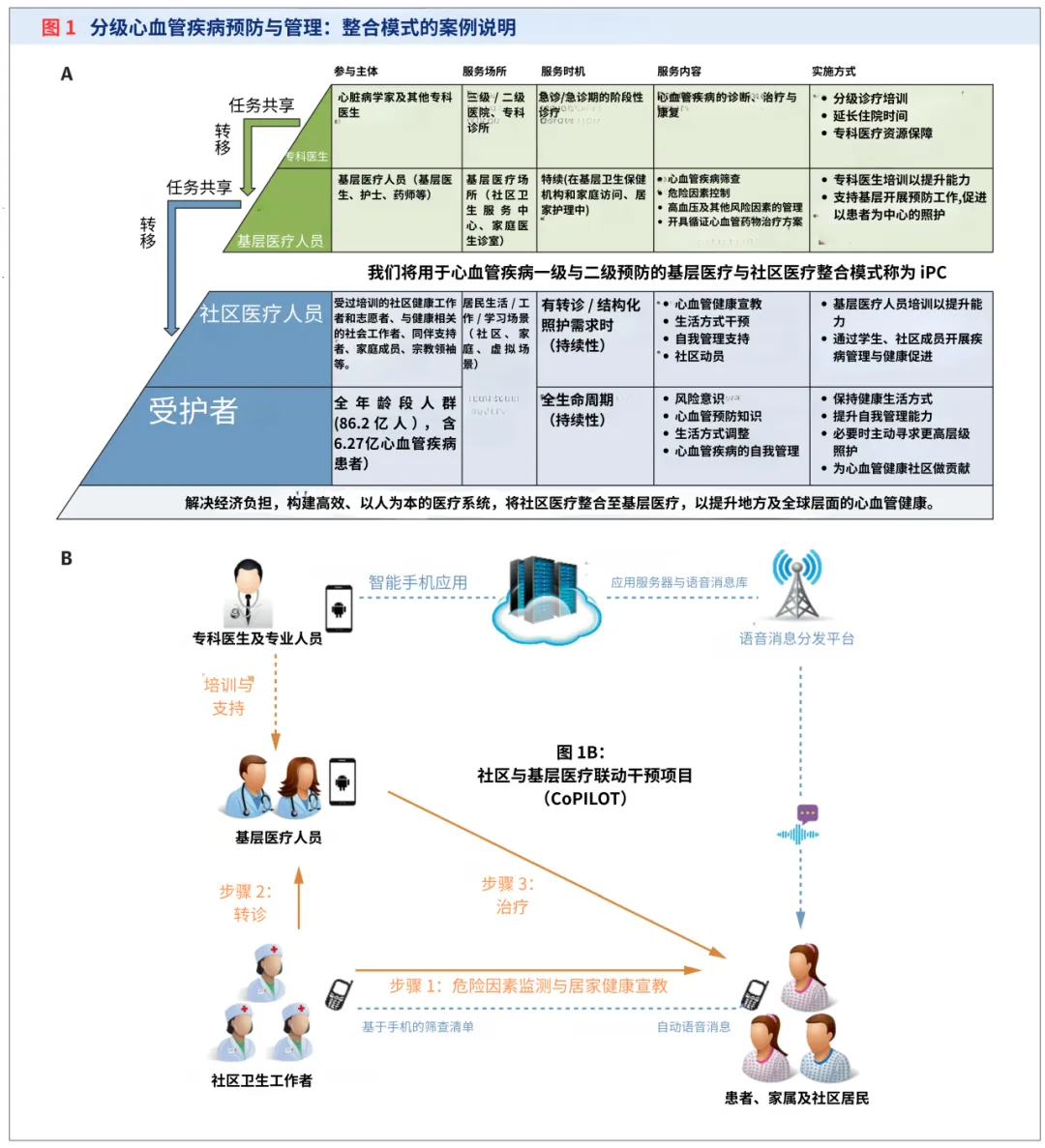

Primary health care (PHC), as the cornerstone of CVD prevention, plays a central role in risk screening, risk factor control, and guideline-based medication management. Community-based care (CBC), on the other hand, is delivered by trained community health workers, volunteers, and peer supporters. These non-specialist providers offer complementary services—such as health education, behavioral interventions, and routine monitoring—within community and household settings outside formal medical facilities.

By integrating PHC and CBC, the iPC model moves away from a specialist-centered approach to CVD management. It shifts the focus from treatment alone to prevention and treatment combined, from purely medical interventions to the inclusion of social and cultural determinants, from episodic acute care to continuous life-course management, and from physician-led, hospital-based services to more accessible, community-oriented care.

Through clearly defined roles, coordinated workflows, and technological enablement, the iPC model breaks down traditional barriers between care settings and provider roles. It enables full-chain coverage—from prevention to diagnosis and treatment, and from hospitals to communities—clearly demonstrating its core strengths of integrated prevention and treatment, multi-sector collaboration, and scalable implementation (Figure 1).

A growing body of empirical evidence supports the effectiveness of the iPC model. The COBRA (Control of Blood Pressure and Risk Attenuation) project, conducted in rural areas of Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, combined home-based health education and blood pressure monitoring delivered by community health workers with training for primary care providers and coordinated referral systems. This multi-component intervention increased blood pressure control rates by 22%. Similarly, in rural China, a primary-plus-community intervention model led by village doctors was shown through long-term follow-up to reduce CVD risk by 27%–29%.

Despite its promise, the implementation of the iPC model faces significant challenges, including limited leadership support, difficulties in cross-sector coordination, insufficient capacity in primary and community care services, low public trust, and inadequate resource allocation for prevention-oriented care. These barriers pose challenges to broader-scale adoption across diverse settings.

The article also addresses common misconceptions surrounding the iPC model, clarifying that it is not a subsidiary of primary care, nor is it equivalent to traditional integrated care. Instead, it emphasizes the model’s complementary resource structure and practical feasibility. The authors call upon researchers, healthcare professionals, primary care practitioners, policymakers, and global communities to collaborate in advancing research innovation, real-world implementation, and large-scale dissemination of the iPC model. Colleagues interested in promoting primary–community integration are welcome to contact Professor Yan at lijing.yan@duke.edu.

Innovation in cardiovascular health extends beyond new drugs and medical devices—it also requires transformation in healthcare delivery models. The integration of primary and community-based care through the iPC model represents a critical lever for addressing global cardiovascular disease challenges and injecting strong momentum toward achieving universal cardiovascular health.